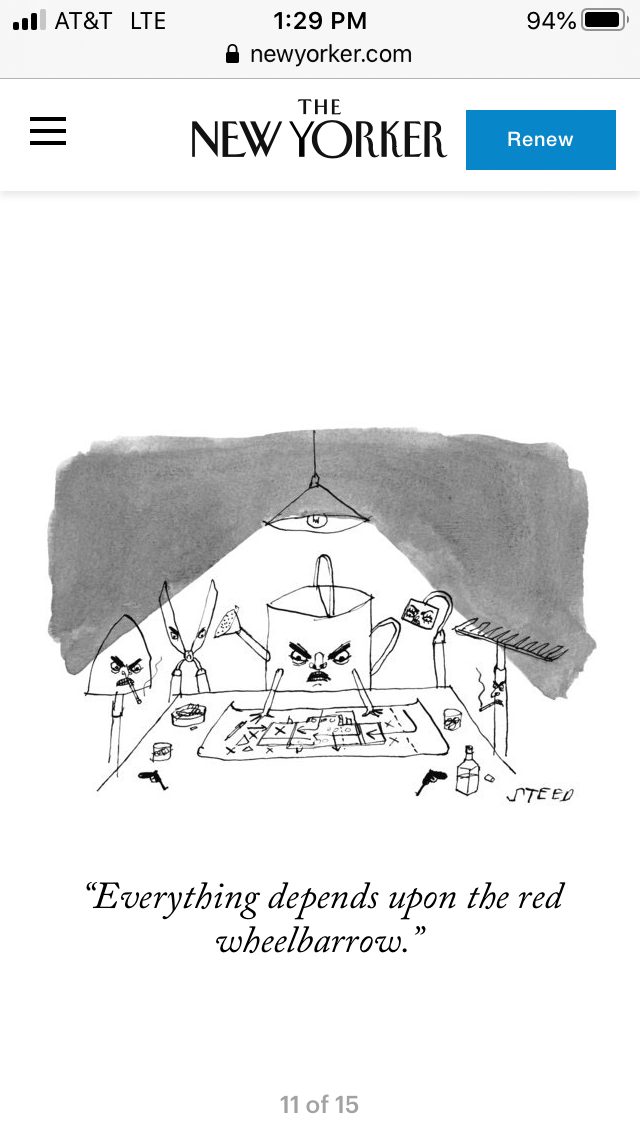

An English Major’s Laugh of the Day

the garden tool gang needs the red wheelbarrow to pull off the garden caper?

So few words. So much class time devoted to it. So dryly demented of Edward Steed to turn it on its head:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45502/the-red-wheelbarrow

sprout said:

I'm sure it's clever, but the maths major doesn't get it.

music/comp-sci here. I have no clue.

The color red is the GOP? I use my wheelbarrow to carry dirt and manure...

PVW said:

I'm still looking for the white chickens.

Distractions, distractions.

A Jersey boy, that William Carlos Williams. Here’s a nice summary, by Adam Kirsch, of what that wheelbarrow was all about before it got mixed up with rakes and hoes.

This is not Williams’s best or most important poem, but it does illustrate some crucial aspects of his art. In his Autobiography (1951), Williams explains that his goal as a writer is to capture the “immediacy” of experience: “It is an identifiable thing, and its characteristic, its chief character is that it is sure, all of a piece and, as I have said, instant and perfect: it comes, it is there, and it vanishes. But I have seen it, clearly. I have seen it.” This is just what he does with the wheelbarrow, the rainwater, and the chickens: trivial in themselves, their sheer uninsistent presence strikes the reader as somehow disclosing the very essence of being. Williams himself, not given to making high claims for his own work, considered this poem “quite perfect”: “the sight impressed me as about the most important, the most integral that it had ever been my pleasure to gaze upon.”

What makes the poem work perfectly is, first, the artistry behind Williams’s apparent artlessness. “The Red Wheelbarrow,” like a number of Williams’s poems (but far from all), could easily be rewritten as prose. Yet the way Williams lays out the words on the page is central to the poem’s meaning. Each couplet starts out narrow and then gets even narrower, with only a single word in the second line; the effect is a measured, haiku-like bareness. And then Williams takes care to break each couplet across a compound word (“wheel/barrow,” “rain/water”) or adjectival phrase (“white/chickens”), disrupting the flow of the language and forcing a hitch or stumble in the reader’s attention.

Most important of all, however, is the wager with the reader introduced in the first line. If you don’t understand why “so much depends” on this quotidian scene, Williams is not going to tell you. As a result, the reader’s ability to intuit the poet’s meaning becomes a kind of test of spiritual fineness, a conspiracy of meaning. If you look at the lingua franca of American poetry today—a colloquial free verse focused on visual description and meaningful anecdote—it seems clear that Williams is the twentieth-century poet who has done most to influence our very conception of what poetry should do, and how much it does not need to do.

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2012/02/23/new-world-william-carlos-williams/

mtierney said:

the garden tool gang needs the red wheelbarrow to pull off the garden caper?

I liked my down to earth concept.

This thread makes me want to go about methodically knocking people's hats off

I have a feeling Max already knows what the remedy for that impulse is. As a precaution, though, I’m holding tight to my Phillies cap.

For Sale

Sponsored Business

Promote your business here - Businesses get highlighted throughout the site and you can add a deal.

.